Coined ‘The Pearl of the Indian Ocean’ it is no surprise that the legacy of Pearl fisheries in Sri Lanka is one closely tied to the identity of the island: spanning as far back as 300 BCE, this industry tells a story of the hegemony and changes within Sri Lanka. This article aims to investigate how the development of mathematical models used in pearl fisheries reflects these undulating forces of power, from indigenous kingdoms to the colonial period.

The Pearl Trade Pre-Colonialism of Sri Lanka

Initially, the pearl trade was controlled by the regional Pandyan King, who used the pearl diving expertise of his subject- the Parava people- to commodify pearls. Mentions of the Parava people in texts like ‘Geographica’ (by Strabo the Greek traveller), indicate the prevalence of the pearl trade to the Roman Empire from the 1st century BCE to the 4th century AD.

Numerical Methods to facilitate the Commodification of Pearl Fisheries

The Mathematical models in this pre-colonial period heavily reflected the trade links and the conversion of pearls into value for the Pandyan Kings.

The most important facet in this time period was classification and then valuation. The method for this was using a “tower” of ten to twelve colanders which were marked with a number, such as 20, 30, 50, 80, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800,1000 (there is no meaning to these markings). The collected pearls were passed through the sieve with the largest holes and the pearls left over were passed down and then passed through the second sieve, and so on until a dust remained at the bottom[1].

Here the text Muttukkaṇakku ironically translated as ‘not pearl calculations’ (a mathematical text created mainly for the purposes of the traders) is used to value the pearls. Using British colonial minister G. Vane’ s interpretation of the text, the valuation process follows.

- First arranging all the given pearls into ten classes;

- Then subdividing based on shape and lustre of the pearl.

- Which led to weighing the pearls of each class separately.

- Then assigning monetary value by factoring in the market price per weight at the time of valuation.

High-quality pearls which were usually found in sieves 20 to 80 were valued in terms of a measure called Cevvu, which is a calculation to apply value to the size of the Pearls. Pearls of inferior value were valued according to their weight in kaḻañcu or Mañcāṭi, which are Tamil units of weight[2].

The market price of the qualified pearls (per cevvu) might depend on the number of years when fishing was halted, and the loss met in the previous year fisheries[3]. It seems that a kind of standardised multiplication table would be used by the pearl dealers at the time of the trade, however this type of valuation did mean that the values of pearls varied between different people and different times.

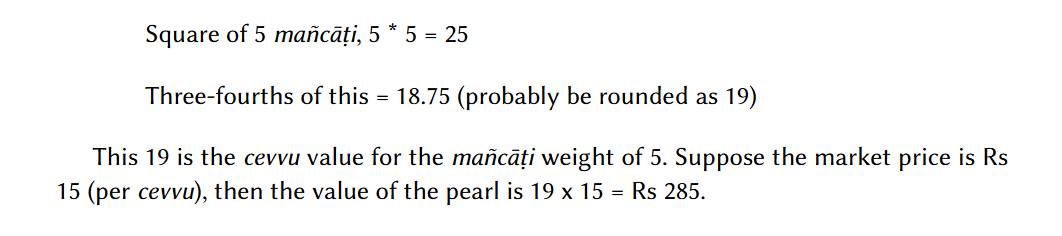

An example follow for a pearl weighing 5 Mañcāṭi. [4]

The arrival of Arabs in Sri Lanka from the 8th to 15th century AD, challenged the pearl trade monopoly of the Pandyan King and the Parava people. To combat this, the Parava people conducted a mass conversion to Christianity to align themselves with, and garner the support of, the Portuguese settlers- who arrived on the island in 1524.

The Pearl Trade During Colonisation

During Portuguese colonisation, the greatest profits were derived in the first half ( 1525 to 1600), where they were able to break the power of the Arabs and exploit the native forces. Their mission was to fuel the demand started by Columbus’ discovery of the rough pearl in 1498- which allowed pearls to be accessible to a greater range of social classes. The key thing with ‘seed’ pearl is that they are harvested from young oysters- which ultimately led to insufficient recovery time and depletion of resources and resulted in long-term abandonment in pearl fisheries in Sri Lanka in the 1640’s.[5]

The Dutch advent in 1658, set out to develop the pearl fishery infrastructure, following this inactivity. A failed fishery in 1700 discouraged investment, prompting Dutch authorities to let the oyster banks rest for eight years. When fishing resumed, rudimentary sampling was introduced a year in advance to assess readiness. This approach led to a successful fishery in 1708, yielding 106,176 florins (approx. £9,000)—on par with British yields nearly two centuries later.[6]

The British assumed control following the fall of Dutch power during the Napoleonic Wars. From then on, the industry was characterized by systematic exploitation and optimization. For example the biggest fishery in Sri Lanka (1905), had a yield of 81,580,716 oysters that gave a revenue of £251,073[7].

This efficiency was mainly driven by new improved numerical methods of sampling employed by the British Colonial Ministers, since the mathematics of valuation was made redundant by the fall of regional kings and the homogenous subjugation of Sri Lankans under the British Empire.

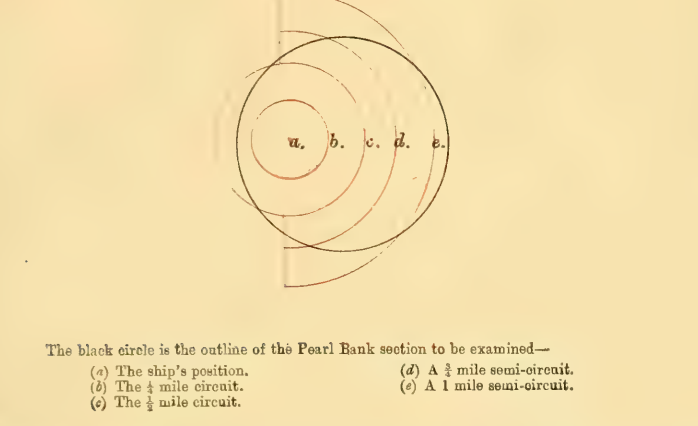

A key sampling method was employed by Captain Donnan called the ‘circle inspection’ method, which was used bi-annually to evaluate the profitability of a fishery.

Circle Inspection method is as follows: [8]

- Four boats made twelve concentric circles over a 1.5-mile-wide area.

- Divers from each boat collected oysters, which were counted and mapped.

- The number of oysters per dive was averaged to estimate population density.

- Samples were shelled and weighed to assess oyster age and pearl development.

- A second inspection was conducted ten days before the fishery to confirm profitability.

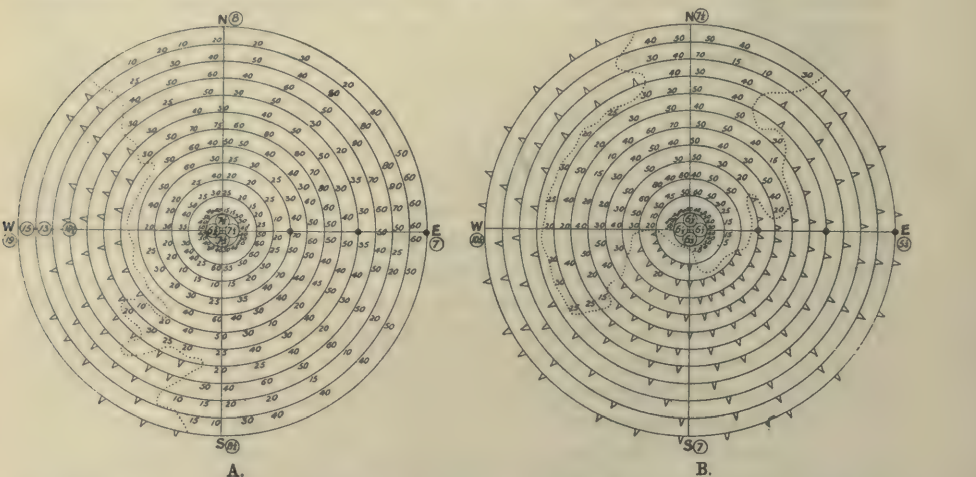

The diagram of distribution of old and young oyster are shown below. [9]

The diagram of the course of boats is shown below [10]

In conclusion, this story proves historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s claim that ‘One can scarcely find an enterprise then that encapsulates the phases of European “expansion” in Asia better than the fishery’. Thus, understanding something as seemingly disconnected as mathematics in Pearl fisheries gives us a comprehensive picture of the history of Sri Lanka itself and the hegemony that has shaped it. Starting from the economic needs of the Pandyan Kings, to the pressing issue surrounding sustainability that drove the need for mathematics during the colonial period and the eventual closure in the 20th century.

[1] Babu, Prakash, Muttuk Kaṇakku: Muttuk Kaṇakkatikāram eṉkiṟa Muttuk Kaṇakku. Page 8, Palm Leaf Press, 2024,

[2] Wikipedia, Tamil units of measurement, 2023, Accessed April 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tamil_units_of_measurement,

[3] Babu, Prakash, Muttuk Kaṇakku: Muttuk Kaṇakkatikāram eṉkiṟa Muttuk Kaṇakku. Page 10, Palm Leaf Press, 2024,

[4] Babu, Prakash, Muttuk Kaṇakku: Muttuk Kaṇakkatikāram eṉkiṟa Muttuk Kaṇakku. Page 10, Palm Leaf Press, 2024,

[5] Siriwardana, T.M., Dissanayake, N.H. & Çakırlar, C. Pearl Fisheries in South Asia: Archaeological Evidence from Pre-Colonial and Colonial Shell Middens around the Gulf of Mannar in Sri Lanka., 960–994 (2024).

[6] Dr Shihaan Larif, History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls – the Organic Gem Perfected by Nature, Page 5, 2021

[7] Dr Shihaan Larif, History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls – the Organic Gem Perfected by Nature, Page 5, 2021

[8] Vane, G., and Herbert W. Gillman. “THE PEARL FISHERIES OF CEYLON.” The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 10, no. 34 (1887): 14–40.

[9] W. A. HERDMAN, D.Sc., F.R.S., P.LS., PEARL OYSTER FISHERIES OF THE GULF OF MANAAR, Page 16, 1905

[10] Hornell, James, Report of the Government of Madras on the Indian Pearl Fisheries in the Gulf of Mannar. Madras: The superintendent, Government Press, Page 85, 1905