Blaise Pascal and the World’s First Mechanical Calculator

Blaise Pascal was one of the world’s most renowned philosophers, inventors, mathematicians, physicists, and all-round smart guys. He lived in 17th century France, born in 1623 and dying at the age of 39, achieving much in his many career paths. He was a child prodigy, observing his fathers work as a tax collector in Rouen had a strong influence on him and created a love for mathematics, which led to one of his most impressive inventions, the Pascaline, also known as the world’s first mechanical calculator.

Pascal’s Formative Years

Blaise Pascal is today considered a child prodigy in many fields of academia, but especially in Mathematics, where he showed great promise at a young age. He was not allowed to learn Mathematics before the age of 15, his father having banned all mathematical writings in their household, adopting a home-schooling approach to the young mind’s education. This changed at age 14 when his father noticed that Pascal had developed his own technique to measure the angles on triangles, unaided. One of the many urban legends surrounding his modern-day reputation is that he learnt advanced mathematics, so he could remain in bed longer in the morning, skipping morning classes. This great interest in mathematics would only increase as Pascal grew older, and he started helping his father with his work as a tax collector in the Norman city of Rouen.

Image credit: Palace of Versailles, CC BY 3.0 DEED via Wikimedia Commons.

The Invention and Practical use of the Pascaline

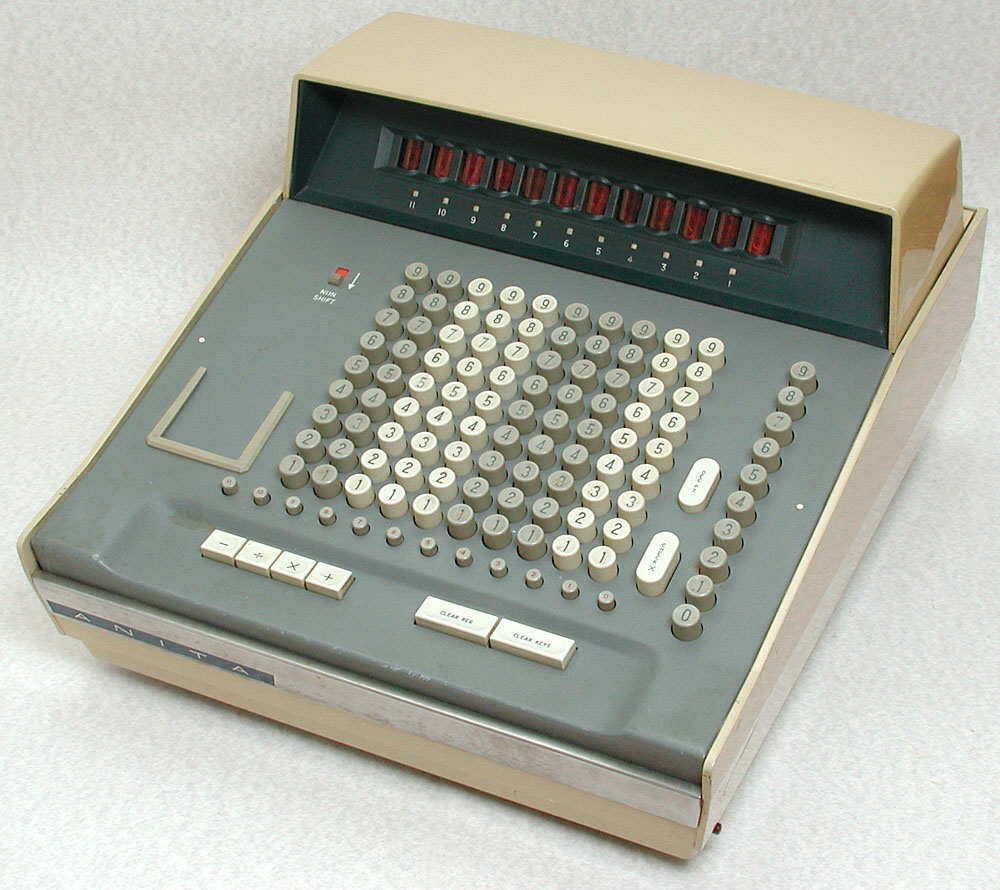

It is in 1642 in Paris, at 19 years old, that Pascal invents the very first Pascaline. Tired of having to see his father do large subtractions and multiplications for his job as a tax collector, he decided to invent a tool to relieve his time-consuming job. He created a box fitted with a complex mechanism, which allowed for the input of large numbers, the Pascaline being able to add, subtract but also multiply and divide through a repeated use of the add and subtract functions. This was a revolutionary invention, but its effects were unfortunately not direct. Only a small number of Pascalines were ever produced (only around 50 models are said to have been totally assembled), meaning that they were rarely found outside of France, but rather that they were bought by wealthy individuals, who would own the Pascaline for its reputation as an expensive and intricate object rather than its intended use.

Image credit: Rama, CC BY 3.0-SA FR DEED via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: MaltaGC, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED via Wikimedia Commons.

A Complex Invention whose Popularity was Limited

Indeed, the price and time it took to create one machine was so great that it could not be mass-produced, especially after the issue of a Royal privilege in 1649, the modern-day equivalent to a patent, given by the French crown to Pascal, which entailed that no one else but him could create a Pascaline. Each machine had to be hand-crafted, and they were delicate pieces of machinery, meaning that a large number of hours had to be spent by Pascal personally to get a finished result, which did not exactly fit the intellectual’s schedule, as he stopped producing them in 1654, only 12 years after the first model had seen the light of day.

In conclusion, philosopher Blaise Pascal is behind one of the world’s most used day-to-day inventions, more than 300 years before the first electric desktop calculator was presented to the public. Even if his Pascaline was not widely distributed and used across the world, it was the first of its kind, saving the user from incredible amounts of time-consuming, hand-written, mathematical operations.

Author

Cyril Corneille