Lady Literate in Mathematics

Throughout history, women have been prevented from accessing higher education, and when access has been granted, they have faced prejudice and impediments. The history of higher education in Scotland is no different. However, an ambitious distance learning scheme administered by the University of St Andrews during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries aimed to challenge the status quo. It allowed women from around the world to study at university level and gain a recognised higher educational qualification, with the study of mathematics an important part of the scheme.

The Push for Female Higher Education

Prior to the nineteenth century, it was rare for women to be admitted to, or receive, a degree from a higher educational institution anywhere in the world. The teaching of university-level mathematics was no exception, and this situation continued well into the mid-1800s. It was argued by some, including women, that studying for and sitting examinations would be detrimental to the physical and mental health of female students, thus threatening their reproductive capability and, by extension, the future of humanity.

The movement for the advancement of female education in the United Kingdom was championed by individuals such as Mary Wollstonecraft in her 1792 book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and nineteenth century politician John Stuart Mill in his essay The Subjection of Women. Under pressure from ladies’ educational associations across the country, higher educational institutions and schemes were created specifically for women.

The first institution to award academic qualifications to women, Queen’s College London, was founded in 1848, and was swifty followed by Bedford College in 1849, now part of the University of London. Furthermore, in 1866 the London Ladies Educational Association successfully pressured the University of London to award higher educational certificates to female students, while the Medical Act 1876 allowed medical authorities to grant licences to any individual regardless of sex. Additionally, throughout the mid to late 1800s, local lecture series were routinely organised for women, often hosted by university academics.

Lady Literate in Arts Scheme

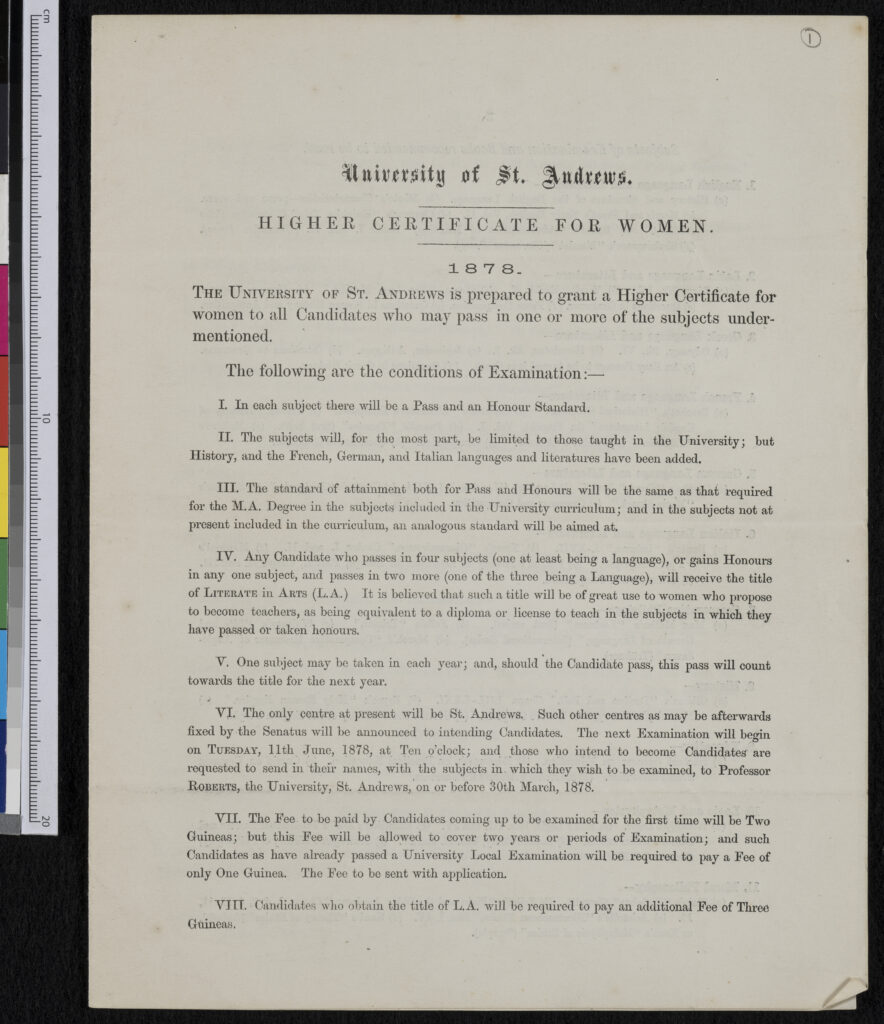

In 1877, the University of St Andrews created the Literate in Arts (L.A.) higher education certificate, a pioneering distance learning qualification aimed at women. The L.A. was initially proposed to the University Senate, the governing body of the University, in 1876, and from 1878 the certificate was presided over by Professor of Moral Philosophy, William Angus Knight. The L.A. was renamed L.L.A. (Lady Literate in Arts) in 1880 due to the University of Edinburgh granting the title of L.A. to students who had attended classes at the university for two years.

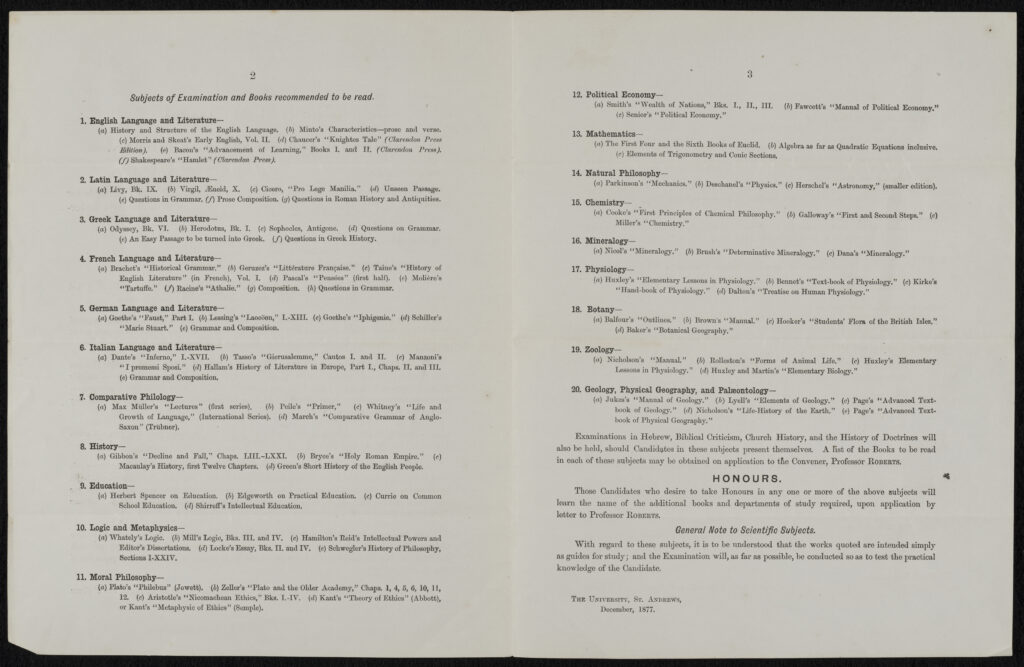

Initially, a wide variety of subjects including mathematics, astronomy, history, French, and German were offered to students, with passes in four subjects (one of which had to be a language) necessary to achieve the L.A.. For the L.L.A., in 1886 the number of subjects required was raised to one each from five groupings; in 1887 it was again raised to seven subjects, with one taken at honours level. This change to the L.L.A. certificate brought it in line with the University’s M.A. degree.

Previous to 1883, examinations for the scheme were held at designated assessment centres in St Andrews, Dundee, London and Halifax. However, a provision to the regulations of the L.L.A. scheme from 1883 onwards allowed examinations to be taken anywhere in the world, provided that a suitable candidate such as a headmistress or church minister could act as an invigilator. Examinations were soon taken in countries such as South Africa, India, and Australia.

The L.L.A. was classed as a diploma but was regarded as comparable to a degree. This viewpoint was made clear by the university in an 1892 statement on the scheme:

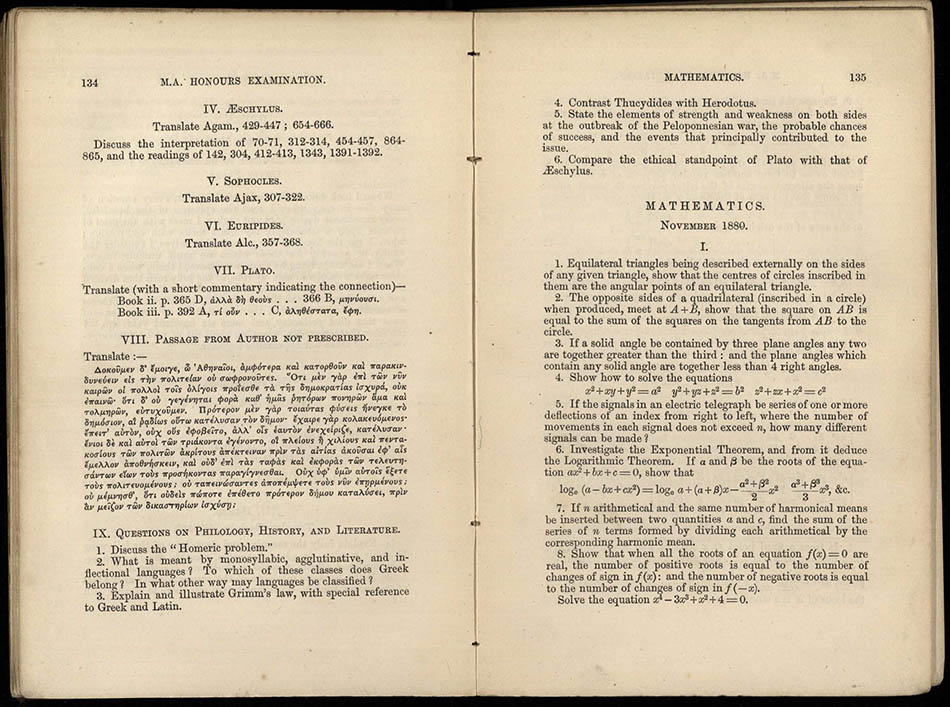

The possession of the L.L.A title by women, while not equivalent in privilege to the procession of the degree of M.A. after attendance at the Classes of the University, shall, nevertheless, be regarded as a University degree, inasmuch as the standard of examination shall be precisely the same as that which Masters and Mistresses of Arts have to pass – the two examinations being simultaneous in time, and in the cases in which the subjects selected by the candidates are those taught at the University, the same papers being given out.

Image credit: University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums.

Women who held the title of L.A./L.L.A. were highly regarded in academic circles. In 1879 the Teacher’s Training Syndicate at Cambridge accepted the L.L.A. Examination as equivalent to graduation, while in 1887 the Ministry of Public Instruction in France viewed certificate holders as eligible to teach in French schools. In 1890 the General Medical Council allowed certificate holders exemption from a preliminary exam for entry to medical school.

Image credit: University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums.

Mathematics and the L.L.A.

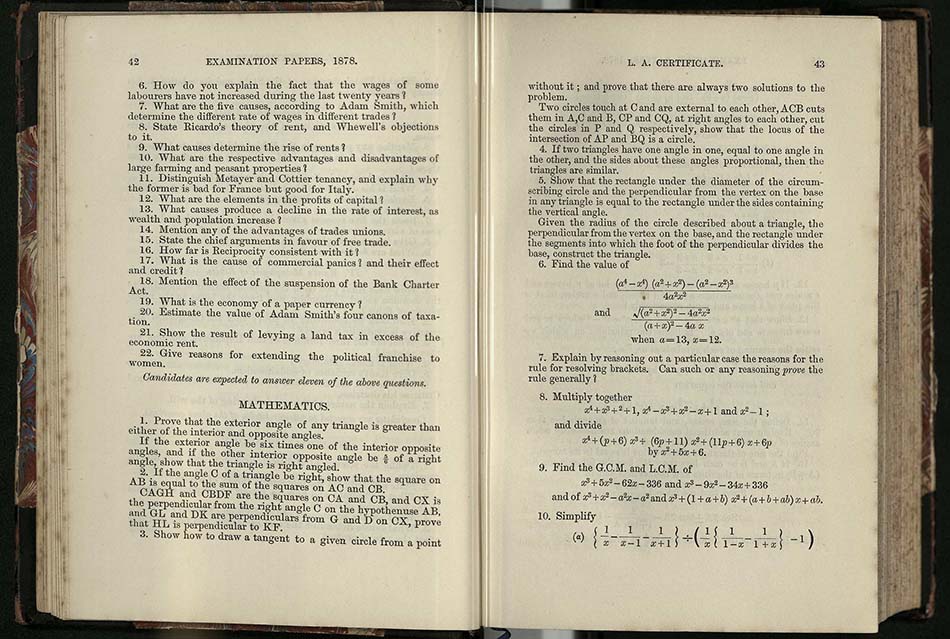

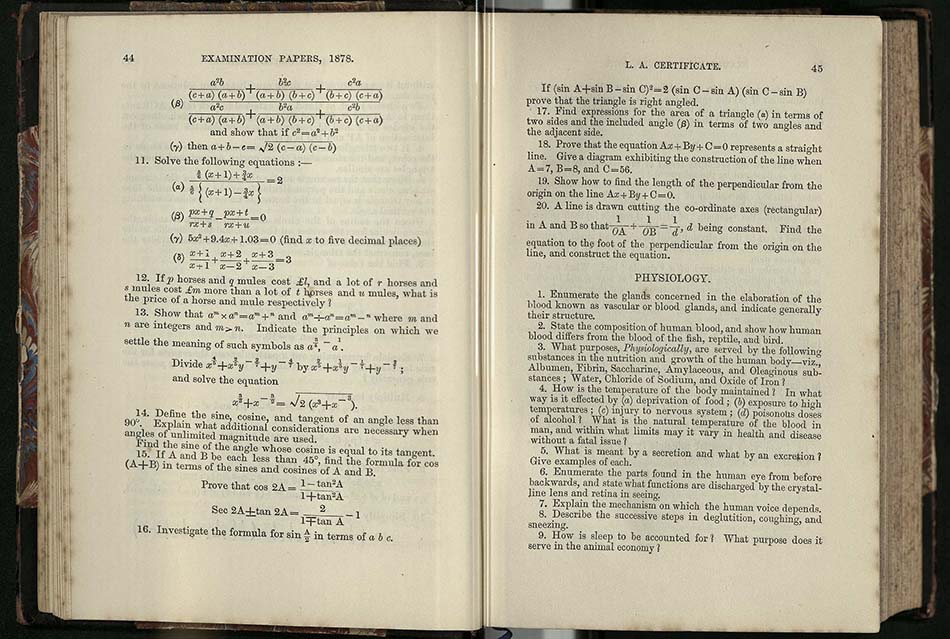

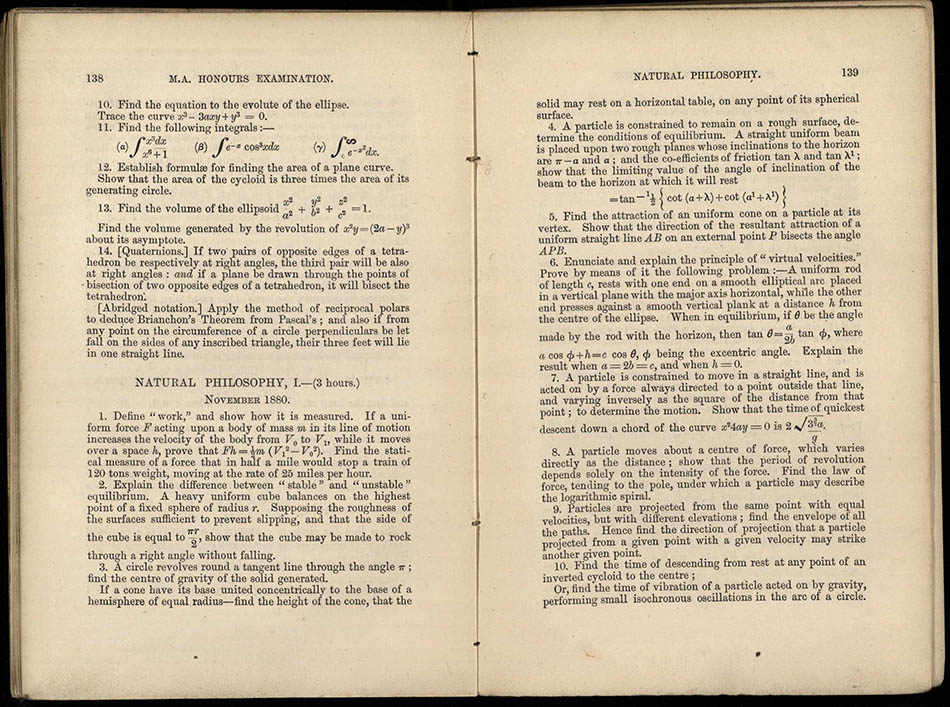

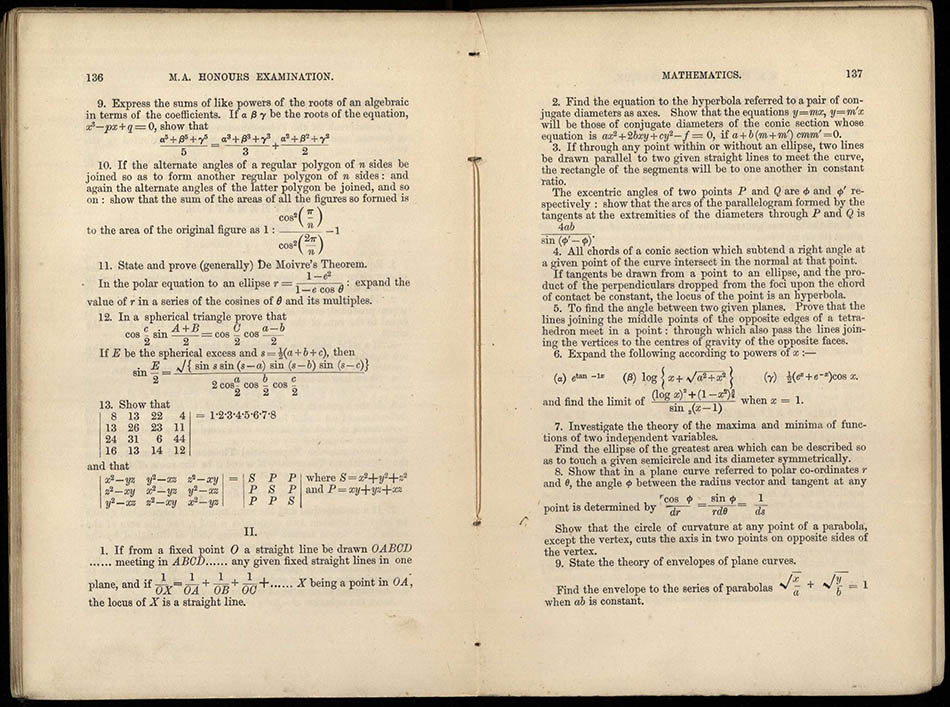

In mathematics, both the L.L.A. examinations and the degree examinations were composed of pass standard and honours standard papers. At pass standard, the L.L.A. and honours papers were similar in difficulty. They each examined the topics of geometry, co-ordinate geometry, algebra, and trigonometry. At honours standard, there were noticeable differences in the material examined. For example, in 1898 the L.L.A. exam paper asked candidates to integrate and differentiate a selection of functions, whereas in 1898 the degree examination asked candidates to solve a variety of differential equations. Additionally, questions on spherical trigonometry and systems of equations were asked in the honours degree examination which were not asked in the L.L.A. honours examination.

The divergence in topics examined at honours level between the L.L.A. examinations and the degree examinations somewhat contradicts the assertion from the university that each qualification was of the same standard. At pass standard the content was indeed identical, however at honours standard the L.L.A. papers were easier. Even so, the material examined in L.L.A. papers was still challenging and is comparable to sections of St Andrews mathematics courses today. For example, in today’s degree programmes binomial expansions are taught in the first year, while diverging and converging series and Fermat’s little theorem are taught in the second year. These topics were covered in L.L.A. examinations. Furthermore, many of the geometry questions would be difficult for current university students to attempt as the relevant material is no longer taught to the required standards. A point of note is that calculus was considered an honours topic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however today it is commonly taught in high school.

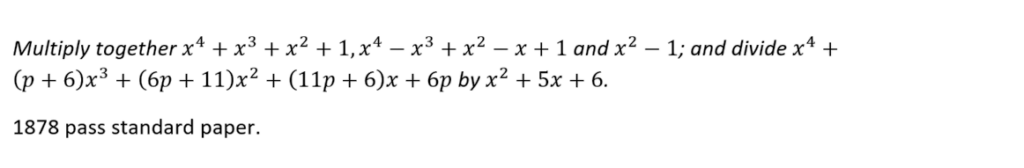

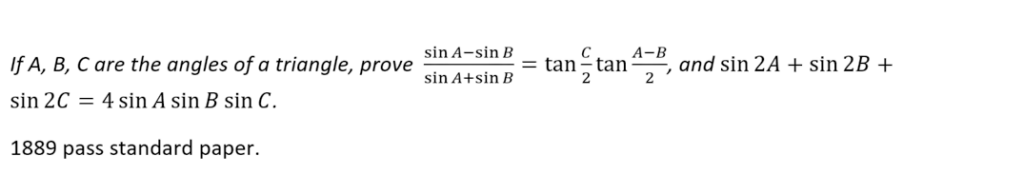

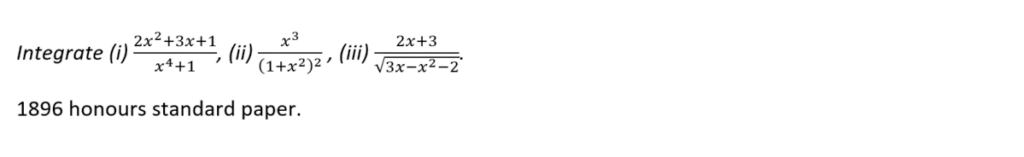

To give a flavour of the type of questions asked of the L.L.A. students, three are shown below:

The above questions demonstrate the complex problems asked of L.L.A. candidates.

Impact of the L.L.A. Scheme

The Universities (Scotland) Act of 1889 challenged the relevance of the L.L.A. scheme, as the act allowed women to attend St Andrews from 1892. However, the scheme continued until its end in 1931. From 1878 until 1931, there were 36,017 candidates, 27,682 subject passes, and 5,117 L.L.A. diplomas achieved. Furthermore, registration fees charged to students generated a surplus of £1,458, equivalent to £148,278.56 at January 2023 rates. This money helped to provide bursaries for female undergraduates after 1892 and contributed to the cost of building of University hall, the first female university residence in Scotland.

The L.L.A. scheme was an innovative and ground-breaking undertaking. It allowed women from around the world to expand their learning and achieve a higher educational certificate, helping many to progress in their careers. The mathematical examinations challenged students’ intellectual capacities and demonstrated their ability to thrive in a demanding subject. It helped to prove that female students were capable of great academic achievements and contributed to the advancement of female education in the UK and across the globe.

Image credit: University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums.

Author

Cameron O’Donnell

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Isobel Falconer, my supervisor at the University of St Andrews, and Rachael Rodriguez, Assistant Archivist at the University’s Special Collections. Your advice and support helped shape the content and structure of this article.