The Hebrew Calendar

When people think of mathematics, they often think about someone in a cramped and stuffy office, locked away from the world. This is not always the case. For most of history, mathematics has been strongly influenced by the society and culture surrounding the mathematician. A notable example of this can be seen in the work of Aaron ben Meir, a Jewish mathematician, and scholar, who lived during the 10th century in the Abbasid Caliphate in what is now modern-day Iraq.

Solar vs Lunar Calendars

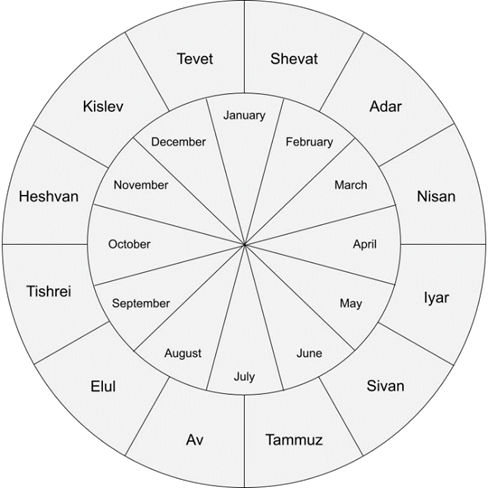

The type of calendar we use today is called a solar calendar which follows how long it takes for the Earth to rotate around the sun. The Hebrew Calendar is lunar, meaning it tracks time by lunar phases (for example, you could track the time it takes to see a crescent moon twice, and from this, you can work out weeks, months, seasons, years, etc…).

One of the advantages of the Hebrew calendar being lunar as opposed to solar, was that farmers could look up at the sky and work out when they needed to harvest or plant. During its development (and for most of human history) many people worked on farms, so using a lunar calendar made more sense. However, one of the problems that Ben Meir faced was that the lunar and solar phases did not match (you could technically be in spring while it was still summer).

Image credit: Baruch Zvi Ring, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Eden Aviv public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Problem

The Hebrew Calendar was developed based on the Babylonian Calendar. In both calendars, an additional month is occasionally inserted to align with the lunar cycles, which tend to drift over time. However, this drifting and the occasional addition of extra months could potentially disrupt Jewish religious practices. Saturday is the day of rest in which all constructive work, including cooking, is forbidden, but if Yom Kippur fell on a Friday or Sunday — a holiday in which Jews fast for 25 hours straight to rid themselves of the previous year’s sins — then people would not be able to feed themselves for 48 hours! Using mathematical calculations, the scholar Hillel the Younger determined that if the leap month were inserted in the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 11th, 14th, 17th, or 19th year within the 20-year Babylonian calendar cycle, it could prevent Yom Kippur from coinciding with either a Friday or a Sunday.

Many years later, in the 10th century, Ben Meir started to see the drifting of the calendar happening again. The calculations for the calendar were taken based on the sky over Iraq and not Jerusalem (the holy city and center for Jewish life), the time difference between the two places — due to the position of the sun and moon — caused the calendar to be off between the two locations. Using observations of the stars over Jerusalem and Iraq, he was able to correctly calculate that the two locations were separated by 8 degrees and 55 minutes longitude. To account for this, he proposed splitting the world into time zones. This was 800 years before railroads made standardised time zones necessary.

The Controversy

Through this calculation, Aaron ben Meir suggested that the date for Passover (a holiday that celebrates Jews leaving enslavement in Egypt) be moved back by about two days. This caused outrage in the Jewish community in Iraq, as they thought no man should move on such a holy day. Ben Meir was warned about such objections by his friends and fellow scholars, but he pushed through and continued to advocate for his proposal. The debate ended with him getting forcefully thrown out of the Jewish community of Iraq. The story of Ben Meir shows that a mathematician does not need to be disconnected from culture to make significant advancements. On the contrary, it illustrates that a mathematician deeply integrated into their cultural context can make groundbreaking discoveries.

Author

Nathan Barnes

Updated By

Eva Devisme