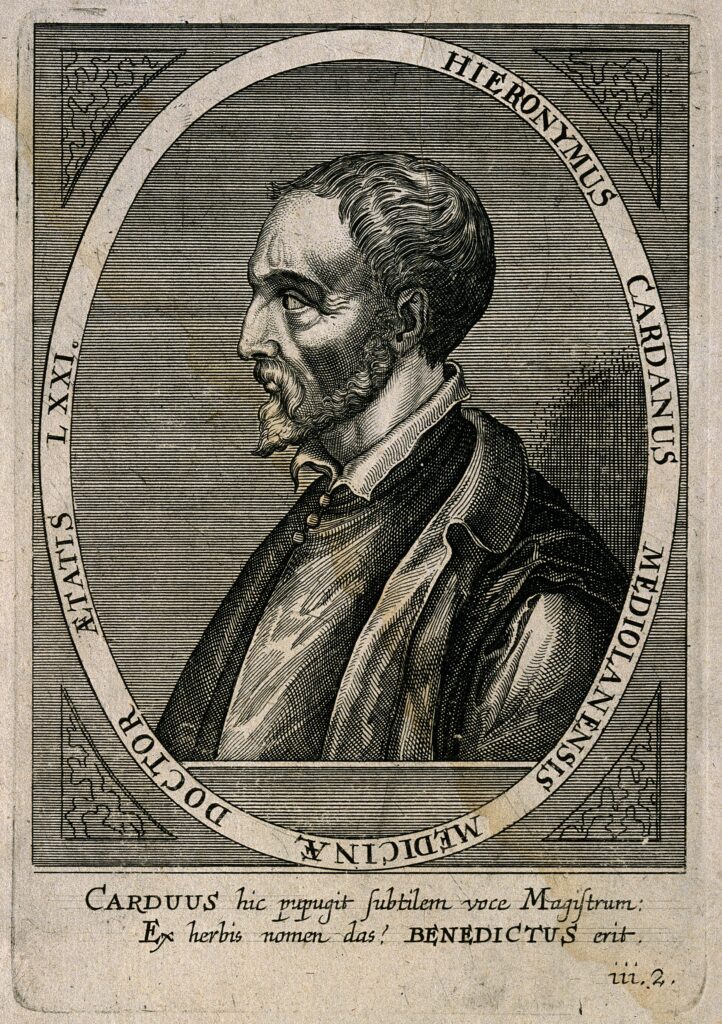

The Strange Life of Girolamo Cardano

Cardano was born 24 September 1501 in Pavia, Italy, the bastard son of a friend of Da Vinci’s. Because of the plague, he was taken from Pavia to Milan in 1505. At nineteen, he returned to Pavia to study medicine. By the age of twenty-one, he was teaching Euclid, dialectics, and philosophy. In 1524 he transferred to the University of Padua. By the age of 24, he was made rector of the University of Padua. Known for being “displeasing,” (his own words), he won the rectorship by only a single vote. He was awarded his doctorate degree in medicine in 1525, but his brash personality meant that the College of Physicians wouldn’t admit him.

Essentially, Cardano was a bit difficult, and everyone knew it.

These setbacks, however, did not keep Cardano from practicing medicine or finding a wife, even if his (illegal, unlicensed by the medical board) medical practice could not provide for him, her, and his gambling addiction. Desperate now, the Cardanos turned to charity.

His luck finally changed when he took his father’s former lecturing position. He continued to treat patients illegally, becoming known for some miraculous cures and growing a group of supporters, who he then used to attack the College of Physicians for continuously rejecting his admission. After publishing a hit-book and being rejected year after year, in 1537 pressure from his supporters finally allowed him entry to the College. This made him so happy he began writing on medicine, philosophy, astronomy, theology and maths.

Then he resigned from his job in 1540 to gamble for two years straight.

After he ran out of money again, from 1543-1552, Cardano lectured on medicine in Milan and Pavia. During this productive period, he wrote his arguably best work, the Artis magnae sive de regulis algebraicis liber unus.

His wife died in 1546, but at least his books were selling well. He became the rector of the College of Physicians. He gained a reputation as a great doctor, being asked for by many powerful people. He only accepted one offer, that of John Hamilton, Archbishop of St Andrews. (Learn more about the seat of bishop of St Andrews at our sister site curious St Andrews!). Travelling to Scotland at the height of his fame, Cardano became the world’s leading scientific celebrity. He cured the bishop and was offered a place at the Scottish court, which he turned down, and over two thousand gold crowns, which he took. After treating this celebrity patient, he was appointed professor of medicine at Pavia University.

Meanwhile, Cardano’s oldest son, Giambatista, married Brandonia di Seroni. Giambattista poisoned her using arsenic and cake, because she publicly ridiculed him. He was executed for this crime, despite Cardano’s best attempts to prove his innocence.

Cardano had trouble moving on from his son’s death. The community turned on him. He moved to Bologna to teach medicine, but this period was full of strife. Cardano’s colleagues tried to get the senate to dismiss him. His other son Aldo, who came with him, was a gambler, and broke into Cardano’s house to steal more money to fuel his addiction. With much regret, Cardano reported Aldo, who was banished from Bologna. His only remaining family was his grandson, Fazio, whom he had adopted.

In 1570, Cardano was briefly jailed for heresy. He had written Jesus’ horoscope, and a book praising emperor Nero, who famously persecuted Catholics. He then went to Rome where the Pope forgave him for his heresy. He wrote more books. He even joined the College of Physicians of Rome, where he lived until the supposed predicted date of his death.

Grafton, Anthony. “Girolamo Cardano and the Tradition of Classical Astrology the Rothschild Lecture, 1995.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 142, no. 3, 1998, pp. 323–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3152240. Accessed 20 Feb. 2023.

ISAR. “Ethical Standards and Guidelines.” ISAR, International Society for Astrological Research, Dec. 2007, https://isarastrology.org/about/code-of-ethics-7-2003/.

O’Connor, JJ, and EF Robertson. “Girolamo Cardano.” MacTutor, University of St Andrews, June 1998, https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Cardan/.

Ore, Øystein. Cardano: The Gambling Scholar, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953. https://doi-org.ezproxy.st-andrews.ac.uk/10.1515/9781400887590

Ptolemy, Claudius. Tetrabiblos. Translated by Frank Egleston Robbins, Harvard University Press, 1940.

Author

Julie Hatfield