Yupanas

We often think of maths as something that comes after the development of some form of writing. However, the Inca Empire, which spanned the countries of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia, shows us just the opposite.

What was the Inca Empire?

The Inca Empire, called ‘Tahuantinsuyo’ in its native language Quechua, was the largest empire in America before the Columbian conquest. It existed from 1438 until 1572, when the Spanish claimed the life of their leader, Tupac Amaru.

The Inca Empire spanned 2,000,000 square kilometres at its largest, roughly equivalent to the size of Mexico. It is perhaps most famously known for creating one of the new wonders of the world, Machu Picchu.

Maths in the Inca Empire

The population of the Inca Empire made use of two devices to satisfy their mathematical needs: the Quipu, and the Yupana. While extensive research has been dedicated to the Quipu, knowledge about the uses of the Yupana is still limited, so we will focus on it.

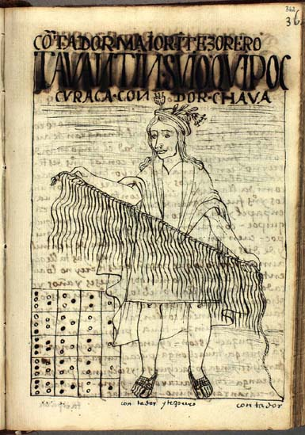

As of recent, two types of yupana have been discovered. To the right, firstly is shown an abacus made of geometrical shapes of differing sizes, where pebbles or corn seeds were placed to make calculations. Next can be seen a resemblance of a 5×4 chessboard, which follows the Fibonacci sequence (1,2,3,5, etc) to make simple calculations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

While researchers are still unsure about the exact uses of yupanas, it is known that they were considered as a mathematical aid to ensure fair trading. Yupanas are believed to have been used for accounting purposes, more specifically by the government to control the supply and storage of resources used to build infrastructure.

Image credit: Scarton, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit:

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Curiously, another use of the yupanas is related to the Inca nobility. Many traces of chili species were found near these, which has caused some archaeologists to believe that yupanas were also used by the social elite to trade the most desired chili species (delicacies) among them.

How do yupanas work?

Focusing on the Poma de Ayala yupanas, these had four to five columns and four rows. The columns represented ten thousands, thousands, hundreds, tenths, and single digits, which can be translated to a simple descending sequence of 10x. The rows, in turn, followed the first four numbers of the Fibonacci sequence (1,2,3,5) to represent the exact quantity of thousands, hundreds, etc. The first row (with one hole) is not used to count, but to remember to carry one unit to the next column when the previous one becomes full.

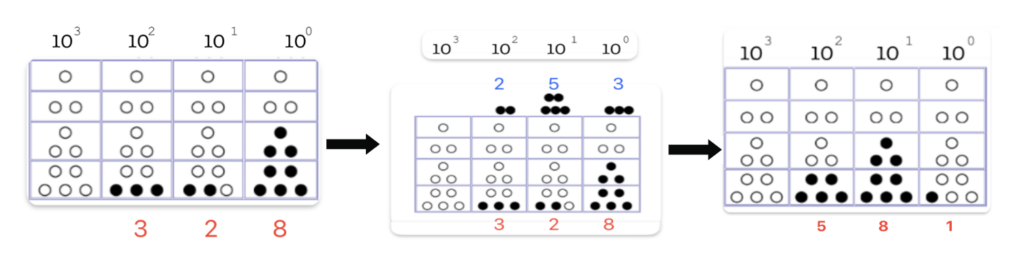

While the Incas used yupanas to perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division accurately, we will focus one specific example. This is: 328 + 253.

Image credit: public domain via Gustavo Velasco Melgar.

First, we place the number 328 on the yupana (first table). Then we place the number 253 on top (second table).

To add these numbers, we simply place the black dots on top of the yupana to their corresponding column. Starting on the column furthest right, 100, we place the dots on the holes, but because it becomes full after the second (as we do not use the top row), we carry one to the next column. We then remove the dots from the 100 column, leaving only the one we still had not counted.

Moving to the next column, we now have 6 dots to place on the yupana, 5 from 253, and 1 that was carried from the previous column. This way, we end up with 8 dots in this column.

Finally, we place the 2 dots in the 102 column to get 5 in total (third table).

Now, we count the new values in the yupana: (5 x 102) + (8 x 101) + (1 x 100) = 581

Due to the nature of the yupana’s numbering system (10x), the Incas were also able to perform calculations involving decimals, by adding columns to the right labelled 10-1, 10-2, 10-3, etc.

What we do not know about yupanas

Despite the many potential uses the yupana may have had during the span of the Inca Empire, there is still much unknown about the level and complexity of mathematics they achieved. Nonetheless, it is certainly impressive that the Incas were able to do this without developing any form of written communications.

O’Connor, J J, and E F Robertson. “Inca Mathematics.” Maths History, 2001. https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Inca_mathematics/.

Pareja, Diego. “Instrumentos prehispánicos de cálculo: el quipu y la yupana.” 1986. Revista Integración, Departamento de Matemáticas, Vol 4, No 1

Selin, Helaine, and Molly Tun. “Yupana.” Essay. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 4592–98. Dordrecht: Springer Reference, 2016.

Tord, Maria Helena. “La Yupana: El Ábaco Inca.” El Comercio Perú, February 17, 2019. https://elcomercio.pe/eldominical/yupana-abaco-inca-noticia-608095-noticia/.

Usvat, Liliana. “Yupana the Fibonacci Number Grid Based Calculator of Inka Empire.” Mathematics Magazine, 2017. http://www.mathematicsmagazine.com/Articles/Yupana.php.

Wikipedia. “Inca Empire.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, February 8, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_Empire.

Author

Gustavo Velasco Melgar